By Aya Adachi & Tatjana Romig

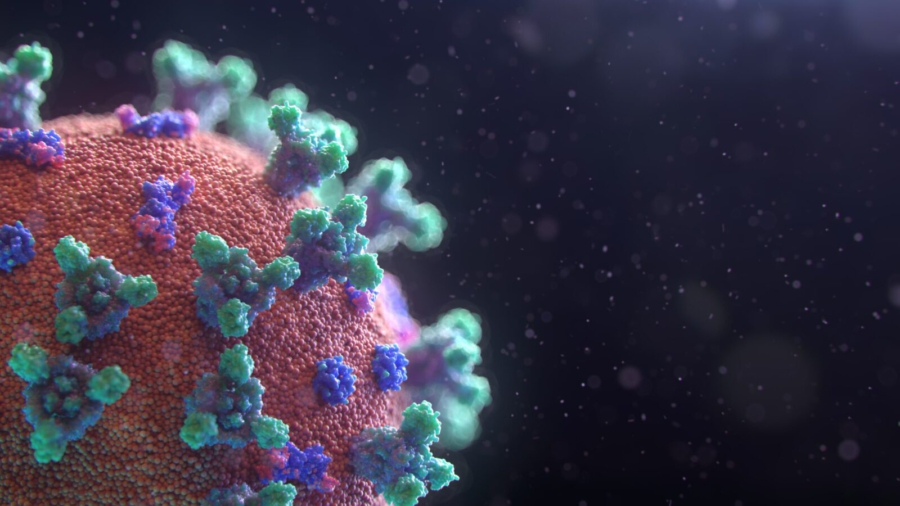

The COVID-19 Virus, which originated in the P.R. China (hereafter China), has spread around the world and caused millions of people to be infected and hundreds of thousands of casualties.

At the time of writing, 20 countries have surpassed China in terms of recorded infections. Globally more than nine million people were registered as infected with COVID-19, with more than two million infections in the United States alone. What started as a local epidemic spiraled into one of the biggest if not the biggest crises after the second world war, impacting not only public health but also economy and society in a way that many could not have imagined just a few months ago. Looking at this reality as China scholars, we can draw two conclusions for our discipline. First, the spread of COVID-19 has exposed China’s role in globalization in an unprecedented way: what happens in China does in fact matter and has implications for the rest of the world. This puts China studies into the limelight, underlining the critical relevance of our discipline. But, secondly, it also shows that in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, the analytical skillset on sufficiently assessing China-related news –and therefore China studies at large– failed to bridge the gap between “China” and “the West” and communicate the urgency of the situation and the global threat associated with it. COVID-19 poses a major challenge to China Studies, one that exposes the flaws of China studies but could also help to reassess our discipline to readjust shortcomings. To this end, we will explore the current state and potential role of our discipline during this time of crisis in a special essay series.

China studies can help to open the black box of the Chinese regime

While it seems that hard sciences are now the ones tasked with solving the crisis, we argue that China scholars have a lot to offer to understand and analyze the course of the pandemic and prevent future global crises.

The crisis management of the Chinese government lacked transparency, which made it difficult for the rest of the world to calculate the risk and magnitude of the virus. More specifically, the authoritarian regime lacks capacity in bottom-up detecting a threat like COVID-19, while being well-equipped to implement measures top-down. The lack of transparency is also signified through media and information censorship and was further exacerbated when foreign journalists of major US news outlets were expelled from China. China scholars can help to open the black box of the Chinese regime and thus contribute to global crisis management through three specific abilities:

1. Language skills offer access

For the majority of China scholars, language training builds the foundation for their regional expertise. This is mainly due to the fact that the ability to read and speak the Chinese language allows access to a different pool of sources. Not all communication materials of the Chinese government are published in English, and if they are chances are high that there are discrepancies between the Chinese and English versions, especially when it comes to politically sensitive parts. Through the ability to assess a diverse set of sources, China studies scholars can see a bigger picture – and thus arrive at different conclusions.

2. Awareness of censorship and the ability to evaluate information

Through research stays in China and working with Chinese sources, China studies scholars gain an in-depth understanding of the difficulties of accessing and evaluating information in and on China. Through this, they are not only acutely aware of the censorship but also able to read between the lines when collecting information. This enables them to evaluate information differently than researchers who have no experience with the restricted access to sources and the guided discursive environment in China. Although the information coming out of China remains opaque, this offers an advantage.

3. Understanding of the authoritarian system

China studies scholars offer in-depth knowledge of China’s authoritarian political system. With political science still largely focused on the study of democracies, authoritarian political systems are less well understood. This bias, combined with the distinctive features of the Chinese political system, often results in simplifications of foreign scholars when it comes to analyzing the political processes and policy responses of the Chinese government. China scholars can add value to debates around the Chinese response to COVID-19 through, for example, contributing knowledge on the interplay of central and local governments during the pandemic, the benefits and flaws of the Chinese health and social system, or the Chinese domestic reality during the outbreak. Hence, while in the current international climate oversimplifications of the Chinese response are prevailing, China scholars can bring a more nuanced analysis of the Chinese regime and its policy response to the table.

China scholars can provide informed analysis

It is important to point out that – given the best attempts to open the black box of the Chinese regime – information coming out of China remains opaque and hard to decode. However, we argue that through the three abilities outlined above, China scholars can provide critical input and information, that adds value to the increasingly polarized debate on the COVID-19 crisis.

This input is not about understanding the Chinese regime or excusing the domestic reality in China but about taking as much information as possible into account to arrive at nuanced conclusions. The critical value of China studies in this time of crisis is thus about providing an informed analysis as a basis for “informed criticism” to policymakers and the general public. Through this, we can showcase the value of critical thinking and academic debates for this crisis and future conflicts.

The following weekly essays will explore different aspects of China Studies in crisis, from a commentary on the polarized discourse to the difficulties when working on China, especially as a junior researcher. If you’re interested in joining the discourse and contributing to this series, please contact the authors at info@mappingchina.org.